Grattan Institute research published today shows the average 25-year-old woman who goes on to have a child can expect to earn A$2 million less by the time she is 70 than the average 25-year-old man who becomes a father. For childless women and men, the lifetime gap is about A$300,000.

This earnings gap leaves mothers particularly vulnerable if their relationship breaks down.

Unpaid work still falls largely on women

The income gap between mothers and fathers is typically due to women reducing their paid work to take on most of the caring and household work.

Even before COVID-19, Australian women were doing 2.2 fewer hours of paid work on average but 2.3 more hours of unpaid work than men every day.

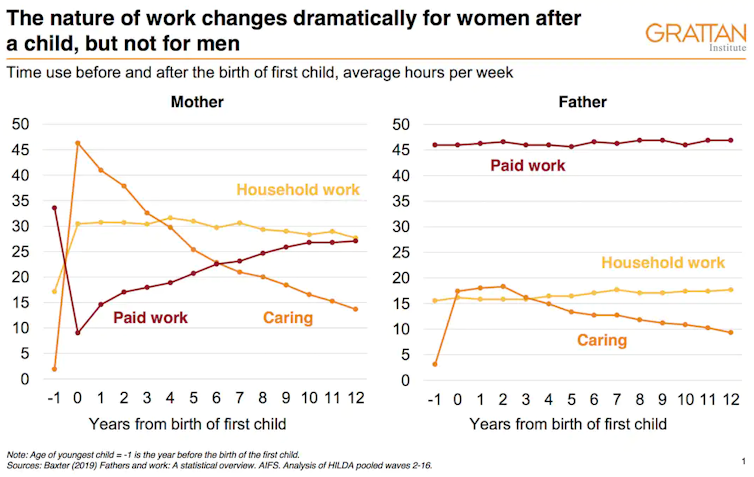

The following chart shows how women’s and men’s time use diverges after the birth of their first child. Mothers typically reduce their paid work to take on the lion’s share of caring and household work. The change for fathers is less dramatic. They continue their paid work and take on some extra caring.

But habits stick. Even a decade after the birth of the first child, the average mother does more caring and twice as much household work as the average father.

When one parent does most of the caring, they become more confident in looking after the child. They know how to change the nappies, what food the child likes, and when nap time is. This knowledge tends to compound, leaving one parent with most of the parenting load.

Dad leave can help

Policy change can help different habits to form. Evidence from around the world – including North America, Iceland, Germany, Britain and Australia – shows fathers who take a significant period of parental leave when their baby is born are more likely to be more involved in caring and other housework years later.

But the Australian government’s paid parental leave scheme encourages a single “primary carer” model. The primary carer is eligible for 18 weeks of Parental Leave Pay at minimum wage (as well as any employer entitlements).

In 99.5% of cases that leave is taken by mothers. Secondary carer leave, called “Dad and Partner Pay”, is two weeks at minimum wage.

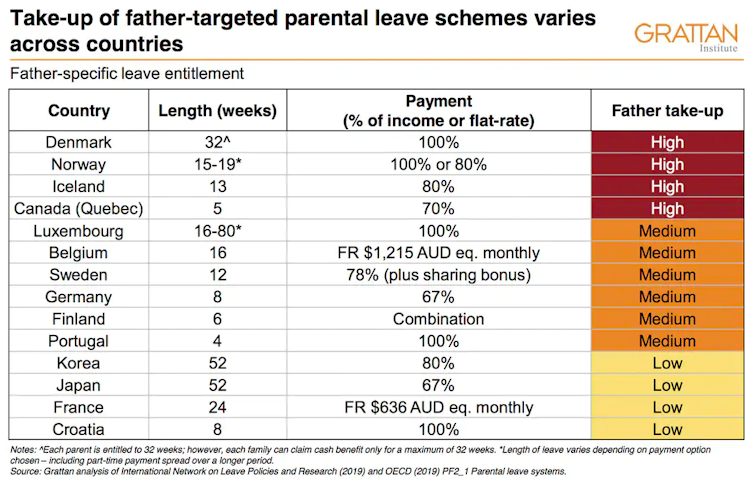

Many other countries provide much longer periods of parental leave for fathers and partners, sometimes referred to as “daddy leave”, as the following table shows.

Iceland, for example, provides three months’ paid leave to each parent and a further three months for them to divide as they wish. Sweden’s scheme entitles each parent to three months of parental leave, plus ten months parents can divide as they wish.

The schemes with the highest take-up typically pay 70% or more of the recipient’s normal earnings, as opposed to the minimum wage Australia’s scheme pays.

But a generous scheme is still no guarantee of success.

Social expectations about different roles for men and women at work and home can still be a barrier. This appears evident in Japan and South Korea. Despite generous schemes offering 52 weeks of leave for fathers, paid at more than two-thirds of normal earnings, just 6% of Japanese fathers and 13% of Korean fathers take parental leave.

A modest policy proposal

For a “daddy leave” scheme to have the best chance of success in Australia, the government would need to spend a lot of money and political capital.

Emulating a best-practice parental leave scheme like Iceland’s would cost at least A$7 billion a year.

A scheme where government payments are linked to an individual’s normal salary would encourage take-up. But the cost would dwarf the A$2.3 billion the federal government currently spends on parental leave, and the biggest benefits would go to wealthy families. Almost all Australian government payments are strictly means-tested, so payments proportional to salary would be a radical policy departure.

One option is a paid parental leave scheme that gives parents more flexibility to share leave. Six weeks reserved for each parent plus 12 weeks to share between them would allow mothers to still choose to take the 18 weeks now provided to primary carers. But families could also make other choices, and fathers would get more time early on to bond with their child and develop their parenting skills.

This would be a relatively cheap reform. If paid at minimum wage like the existing scheme, it would cost at most an extra A$600 million a year.

Baby steps to equality

Reforming Australia’s paid parental leave is not the first and best option to increase women’s workforce participation. Our research shows changes such as making child care more affordable are likely to deliver more bang for buck.

But there is still a case for modest reforms to parental leave. Though it might not be a game-changer for women’s workforce participation, if constructed properly it will have some effect.

This is supported by evidence from Quebec’s parental leave scheme. Introduced in 2006, it included five non-transferable weeks for fathers, paid at about 70% of their usual salary. A 2014 study found it led to mothers, on average, doing an extra hour of paid work a day, earning an extra US$5,000 a year.

More fathers taking parental leave is also worthwhile in its own right, promoting greater sharing of the unpaid workload within families and giving fathers more time with their kids.

Think of it as a baby step towards greater time and earnings equality between women and men in Australia.